Public Safety Alternatives

Violence as Black Public Health Emergency: Social and Religious Aspects and Responses

By: Juard M. Barnes

There is growing alarm across urban America, and especially within communities-of-color, about high levels of largely gun-related violence. The three leading causes of death in the United States for people ages 15-34 are unintentional injury, suicide, and homicide. These violent deaths are, more often than not, directly associated with firearms, and blacks have been impacted disproportionately by violence and by gun-related violence in particular.

.webp)

The trajectory of violence receiving the most public attention and outrage has been police violence against black persons. Between 2015 and 2018, 63 percent of unarmed persons killed by police in the U.S. were racial minorities, with 36 unarmed black males in 2015 and 19 in 2017 killed by police in those two years alone.

Black interpersonal civilian violence also has received wide media coverage. Of the 11,078 U.S. firearm homicides reported in 2010, blacks were the victims in 55 percent of the cases, despite being only 13 percent of the U.S. population. Moreover, 2013 data by the Centers for Disease Control list homicide as the fifth leading cause of death among African American males.

What We Believe

This essay explores violence as a public health problem, noting violence is often bred by poverty, and examining strategies for improving health and educational outcomes for low-income children and families. The essay focuses specifically on faith-based community organizing via a hospital-based violence prevention project in Indianapolis which facilitated a precipitous drop in recidivism, a 30 percent drop in the county jail population over a three-year period, and a $56m public transit measure that changed employment opportunities across the region.

.webp)

Public Health Dimensions

Violence is being regarded increasingly as a public health problem within the United States. As violence prevention scholars point out, prior to the 1980s violence was rarely characterized as a public health matter. But spikes in violence during the 1980s drew heightened attention from public health experts and public policy leaders, producing high-level responses such as the establishment of a Violence Epidemiology Branch within the Centers for Disease Control and generating policy papers and official recommendations from the National Research Council, the Institute of Medicine, and the U.S. Surgeon General’s office.[1]

People who survive violent crimes endure physical pain and suffering and may also experience mental distress and reduced quality of life. Repeated exposure to crime and violence may be linked to an increase in negative health outcomes. For example, people who fear crime in their communities may engage in less physical activity.

[1] Linda Dahlberg and James Mercy, “The History of Violence as a Public Health Issue,” Centers for Disease Control, 2009, 1-2; https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/history_violence-a.pdf

As a result, they may report poorer self-rated physical and mental health. One study found that people who perceive their environment to be less safe from crime may also have higher body mass index scores and higher levels of obesity due to reduced physical activity.[2]

Exposure to violence in a community can be experienced at various levels, including victimization, directly witnessing acts of violence, or hearing about events from other community members. It can also include property crimes that result in damage to the built environment. Crime rates vary by neighborhood characteristics. Low-income neighborhoods are more likely to be affected by crime and property crime than high-income neighborhoods.

[2] Luisa Borrell, Lisa Graham, and Sharon Joseph, “Associations of Neighborhood Safety and Neighborhood Support with Overweight and Obesity in US Children and Adolescents,” Ethnicity & Disease, 26/4, Autumn 2016: 469-476

Risks of Violence

Children and adolescents exposed to violence are at risk for poor long-term behavioral and mental health outcomes regardless of whether they are victims, direct witnesses, or hear about the crime. For example, children exposed to violence may experience behavioral problems, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Children exposed to violence may also show increased signs of aggression starting in upper-elementary school. Children exposed to several types of violence over long periods of time are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and behavioral problems compared to children with only moderate exposure to violence.[3]

The effects of exposure to violence in childhood may be seen in adulthood and can result in greater risk for substance use, risky sexual behavior, and unsafe driving behavior. Individuals exposed to violence at any age are more likely to engage in and experience intimate partner violence. Women exposed to intimate partner violence have an increased risk of physical health issues such as injuries, and mental health disorders such as disordered eating, depression, and suicidal ideation.

[3] National Institute of Justice, “Compendium of Research on Children Exposed to Violence (CEV) 2010-2015, June 2016; https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249940.pdf

.webp)

.webp)

There are serious short and long-term health effects from exposure to crime and violence in one’s community. Addressing exposure to crime and violence as a public health issue may help prevent and reduce harm to the individual and community health and well-being. Additional research is needed to increase the evidence base for what works to reduce the effects of crime and violence on health outcomes and disparities.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a common, potentially disabling, underdiagnosed, and under-treated illness. Primary care physicians assume a critical role in the diagnosis, treatment, and referral of African Americans with PTSD since mental health access is limited for this population. Most African American adult primary care patients with PTSD were either

undiagnosed or undertreated. Both individual (provider and patient) and system-based changes will be required to meet the demonstrated clinical need.[4]

[4] Emily Goldmann et al, “Pervasive Exposure to Violence and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in a Predominantly African American Urban Community,” Journal of Trauma Stress, 24/6, December 2011: 747-751

A Multi-Sector Response

Approaching violence as a public health issue mobilizes a vastly wider range of conceptual and institutional resources in response to the problem, expanding responses far beyond typical law-and-order strategies. That expanded range includes physicians and mental health workers and places them at the forefront of the expertise deployed around these issues.[5] It is also important to point out, however, that designations of violence as a “condition,” requiring “treatment,” repositions this problem in ways that encourage a broader array of behavioral change approaches—including in ways central to the work and ministries of faith communities.

For more than thirty years I have directed The Rehoboth Project, a faith-based organization committed to meeting myriad needs of urban residents. For much of that time, TRP has approached inner-city violence and the status of incarcerated persons as public health travesties. Because violence is a multifaceted problem with biological, psychological, social, and environmental roots, TRP has confronted it on multiple levels at once, with each level in ecologies of violence representing a level of risk and a key point for intervention.

[5] For more on this, see for example a special-themed issue of the AMA Journal of Ethics focusing on “Violence as a Public Health Crisis,” edited by Lilliana Friere-Varga, January 2018; https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/violence-public-health-crisis/2018-01

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

Dimensions addressed within this model include:

-

individual risk behaviors;

-

violence risks within interpersonal relationships and family contexts;

-

violence risks within public places such as schools, workplaces, and neighborhoods; and

-

adverse cultural attitudes and practices, including gender inequality.

Steps to mitigate violence increasingly depend upon multifaceted and multisector approaches to these intersecting risk factors, requiring partnerships between healthcare providers, police, educators, social workers, employers, and government officials. Religious leaders and organizations have a role to play in their pastoral work and, in appropriate cases, by offering their good offices to mediate in specific problems.

TRP’s work has revolved around the recruitment of credible messengers to reach out to potential victims and perpetrators in order to facilitate dialogue among them about alternatives offering a violence-free life. In collaboration with organizational partners such as California-based LiveFree, Faith in Indiana, The Collective, The Health Alliance for Violence Intervention, and others, TRP seeks to:

-

lay the groundwork for proven gun violence prevention models;

-

garner violence reduction policy commitments from policymakers;

-

mobilize clergy, congregations, and community leaders as partners, while providing them with training in effective violence reduction;

-

encourage media framings on gun violence prevention that amplifies the voices of those in communities hardest hit by gun violence; and

-

scale-up advocacy and education work at state and regional levels around policy responses to interstate gun trafficking;

Building upon TRP’s networks and approaches, I worked during a four-year period with an Indianapolis hospital, Wishard Hospital (now renamed Eskanazi Hospital), on a violence reduction initiative called Prescription for Hope. The objective of the project was to intervene in the lives of people who had been shot, stabbed or otherwise injured through violence, and reduce the rate of repeat violence in their lives.

The program engaged in a thorough processing of each violence-related patient upon intake at the hospital, noting medical history, criminal history, and neighborhood residence. These categories were important indicators of both the current instances of violence and of potential future instances as well, given what is known about ecologies contributing to gun violence within the United States. Five key indicators for likelihood of involvement in gun violence are: (1) being a black or Latino male, aged 18-35; (2) significant involvement with the criminal justice system; (3) membership in a street gang; (4). Having had a close friend or family member shot within the previous 12 months; and (5) having previously been shot themselves. With these indicators in mind, the program intake processing often revealed areas of susceptibility to ongoing violence, either for the current client/victim or for someone associated with this person. As a result, some of these associates would be brought into the program based upon information gathered from the initial client.

.webp)

Clergy and Congregations

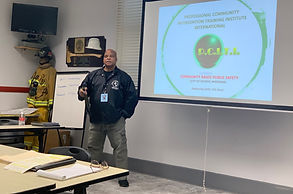

The process included reaching out to pastors throughout the city. Some of them were engaged in various forms of work on. Human services, street walks, crisis intervention. We conducted scores of 1-1s. After a while, we began to conduct training. During those pieces of training, we shared the concept of violence as a public health crisis. Each training featured the stories of affected folks, and a deep dive into the various national models, including Ceasefire, Cure Violence, The HAVI, and Advanced Peace.

Additionally, we gathered to interrogate the importance of team building, within churches, and among faith leaders. The premise is that we must build power and cooperative institutions to insure a well-executed, sustained fight for the justice it takes to dismantle the systems that mitigate against safety in Black/poor communities.

The role of law enforcement

During the introduction to a CVI process, we met regularly with police to explain the community led frame in CVI. We invited municipal workers to other cities (mainly Oakland, CA) to witness the model.

While in Eskanazi (Wishard) Hospital, there were several police officers in our office for nearly 5 years. The relationship remained a one-way information highway. We were never asked to provide information. However, we were given valuable information concerning clients/patients that proved to be very helpful, both on the ground and as things related to data collection.

At the project’s inception, the recidivism rate for victims of violence treated by Wishard was approximately 32 percent. Through engaging clients in intensive case management for a period, of approximately 12-18 months, the program saw recidivist violence among these intakes reduced to a rate of 4 percent.

Pilot programs such as this one can provide means for testing ideas and for a range of partners to become accustomed to working together. This collaboration between TRP’s church-based network, a local hospital, and various criminal justice-sector workers demonstrates that when a problem such as violence is approached in the broad ways possible when characterized as a ‘public’ health crisis, impressive results in responding to the problem are possible.